I’m not a member of any political party. I’ll write more about this another time, but it’s my belief that such organisations are no longer fit for purpose in the modern age. Too much about them is inconsistent with effective representative democracy. And they carry too much baggage, as do all the ‘isms’, ‘ites’, and other labels we too easily, unthinkingly, reductively, and reflexively apply to so many things, and to people. We live in the 21st century, not the 19th.

I reject terms like ‘socialist’, ‘centrist’, and ‘neoliberal’ because, rightly or wrongly, they repel or confuse at least as many people as they attract. They cover complexity and negate nuance. And in doing so they hide the truth.

Because ultimately there’s only one meaningful division, which has nothing to do with politics or theoretical systems. It’s purely about values. What truly matters to you, above all else? The wellbeing and rights of people, animals, and the planet? Or unrestrained profit margins and raw power without social responsibilities?

Having said that, I’m not suggesting we throw the baby out with the dirty old bathwater. Marxists and others have accurately described reality while openly applying values. I came across some writing from 1845 by revolutionary socialist Friedrich Engels the other day, and it couldn’t be more timely.

Under the cover of context

It’s long bothered me that the UK claims to be a collection of nations operating under the rule of law, when its laws so patently do not apply equally to all. The phrase is yet another fig leaf, a plaster over a gaping chasm of injustice.

Take the handling of actual shit, for example. If I let a dog poo on a pavement and don’t pick it up, under The Dogs (Fouling of Land) Act 1996 I can be liable for a fine of up to £1000 if it goes to court. But the privatised water companies can discharge human waste into lakes, rivers, and seas – as they increasingly have: such ‘spills’ in England alone more than doubled in 2023 – with few to no consequences, while their CEOs and shareholders grow ever wealthier.

Just one of hundreds of examples I can think of, in which something penalised heavily when done by regular individuals is ignored or even rewarded in a different context, often one involving the rich and powerful.

The Labour Party repeatedly promised ‘change’ in its successful drive to win power in the UK last year. Yet among some reasonable and necessary policies, their government has continually punched down instead of up, just like the Conservative governments of the last 15 years.

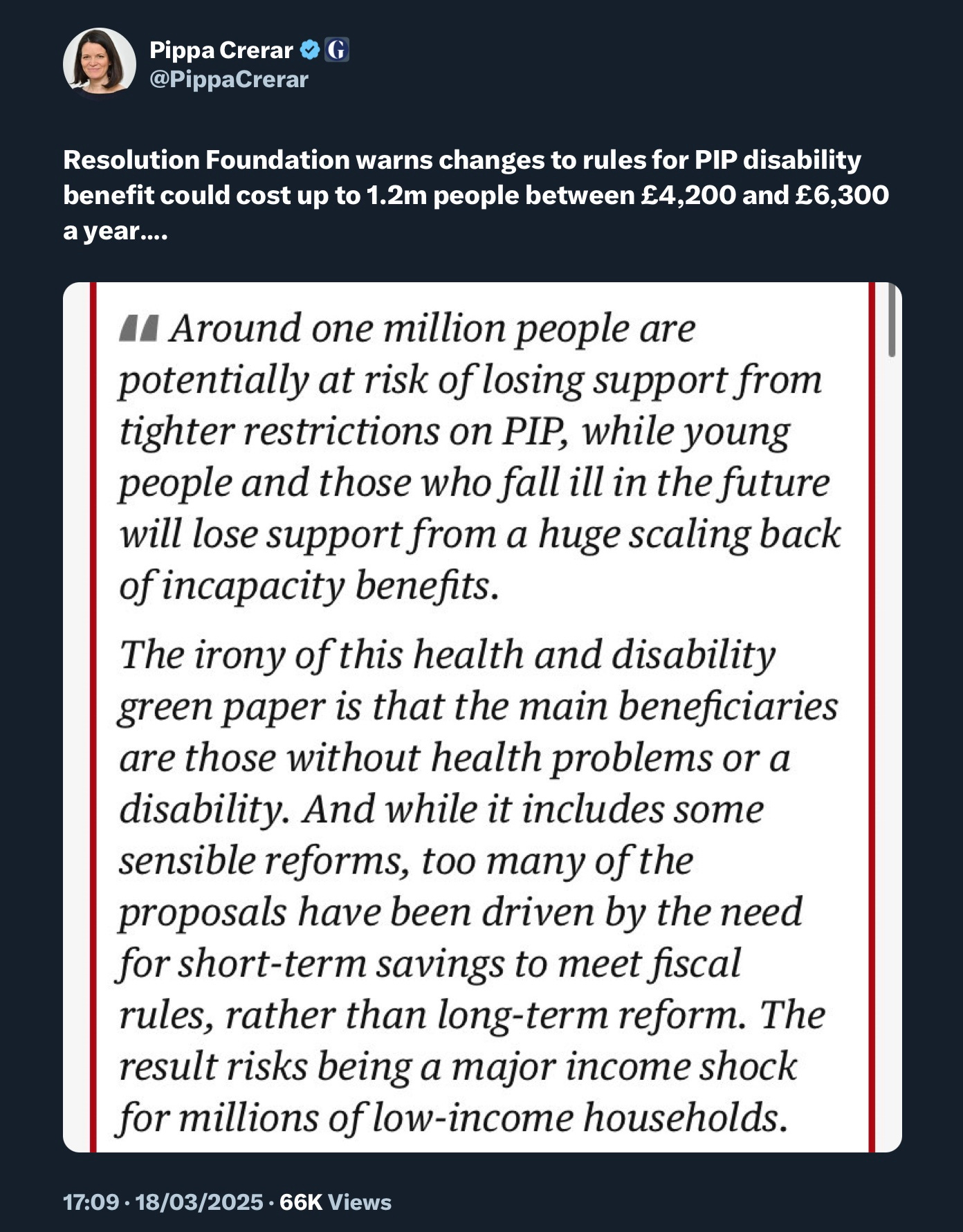

Many people are rightly commenting now, after the government announcement of further cuts to the ‘benefits’ that already inadequately support the most vulnerable people, about how public finances could be improved by taxing the richest more, including the huge corporations that pay lawyers and accountants to help them make no contributions whatsoever. Another example of the rule of law being made inoperable by changing the context.

But I want to focus on another such inconsistency exposed by looking at these proposed cuts and changing the context: the fairly serious matter of death. If I kill one person, and am caught and prosecuted, I will be imprisoned for a very long time. But if a government pursues policies that existing research reliably predicts will kill hundreds of thousands of people in a society, and in a highly uneven way, that’s completely fucking fine, apparently.

Social murder

Engels got there long before me, I’ve discovered. It’s in his Condition of the Working Class in England, published 180 years ago.

“When one individual inflicts bodily injury upon another such that death results, we call the deed manslaughter; when the assailant knew in advance that the injury would be fatal, we call his deed murder. But when society places hundreds of proletarians in such a position that they inevitably meet a too early and an unnatural death, one which is quite as much a death by violence as that by the sword or bullet; when it deprives thousands of the necessaries of life, places them under conditions in which they cannot live – forces them, through the strong arm of the law, to remain in such conditions until that death ensues which is the inevitable consequence – knows that these thousands of victims must perish, and yet permits these conditions to remain, its deed is murder just as surely as the deed of the single individual; disguised, malicious murder, murder against which none can defend himself, which does not seem what it is, because no man sees the murderer, because the death of the victim seems a natural one, since the offence is more one of omission than of commission. But murder it remains. I have now to prove that society in England daily and hourly commits what the working-men's organs, with perfect correctness, characterise as social murder, that it has placed the workers under conditions in which they can neither retain health nor live long; that it undermines the vital force of these workers gradually, little by little, and so hurries them to the grave before their time. I have further to prove that society knows how injurious such conditions are to the health and the life of the workers, and yet does nothing to improve these conditions. That it knows the consequences of its deeds; that its act is, therefore, not mere manslaughter, but murder, I shall have proved, when I cite official documents, reports of Parliament and of the Government, in substantiation of my charge.”

There is no law against social murder, at least not by that name. Nor is there a prohibition against ‘democide’, a term created by the Holocaust historian and statistics expert RJ Rummel for his 1994 book Death by Government to describe any murder of any number of people by any government. Rummel stated that democide – not war, nor genocide – was the leading cause of 20th-century unnatural death.

However, Rummel’s focus was on ‘political’ deaths. ‘Politics’ is another phrase I’m wary of, because simply calling something ‘political’ waves it away, covers it with a massive and instant facade that prevents us complaining or looking any closer. If deaths are the result of political choices, does that make them okay? Why? What about economic choices?

The invisibility of austerity as social murder

As I’ve written elsewhere:

“Research by the International Inequalities Institute, King’s College London, and LSE says austerity spending cuts by successive governments led to the average person losing almost six months of life expectancy from 2010–2019 – women two more months than men. “The North East of England, the East Midlands, South Wales, and the Glasgow City Region were among the hardest hit.”

Other research from the Institute of Health Equity (IHE) at University College London calculated excess deaths using the 10% of wealthiest areas as a baseline. In the peak years of austerity (2011–2019), 1,062,334 people died earlier than if they’d lived in those areas. The deaths were attributed to health inequalities, 148,000 directly due to austerity measures.

Glasgow Centre for Population Health and University of Glasgow research attributed 335,000 excess deaths to “the austerity policies pursued by the UK government since 2010 … the main cause of the decline in the rate at which life expectancy has increased”.

1,062,334 souls. Compare that to those lost in world war two at home and abroad: 454,000. But there’s no annual poppython for austerity deaths, no wall of hearts, no ‘Portraits of Grief’.”

That’s just up to 2019. Additionally, more people in the UK died of Covid than would have without the years of preceding austerity, as the deadly project left the NHS less able to respond effectively to a once-in-a-century pandemic. From 2019 onwards it’s ever more difficult to quantitatively unpick the consequences of that deadly alphabet – Austerity, Brexit, Covid, Disability, Economic ‘decline’. It’s perfectly possible to track the rich getting richer though, yeah? Loadsamoney.

The definition of murder is the unlawful killing of a human being with ‘malice aforethought’ – intent to kill or cause grievous bodily harm. Austerity is already proven to fall far harder upon the heads of people on low incomes, marginalised communities, and especially on women and children.

‘Worsened poverty’ means death, aside from all the misery imposed on the living. More avoidable death. (And not for the ‘comfortably off’, of course, or those wailing about having to pay VAT on private school fees or more-favourable-than-normal inheritance tax on farm properties).

If you know this, you know full well that austerity has inequitably killed a lot of people, because there’s mountains of research on it, and if you choose to impose more of it anyway because ‘growth’, are you not guilty of murder?

Crimes against humanity

There is, arguably, a law against social murder internationally. It’s called crimes against humanity. According to its governing document, the Rome Statute, eleven crimes can be charged as such if “committed as part of a widespread or systematic attack directed against any civilian population”. These include murder, “persecution against any identifiable group or collectivity”, and “other inhumane acts of a similar character intentionally causing great suffering, or serious injury to body or to mental or physical health”.

This body of law is complex, and its application has mostly been restricted to appalling and violent situations such as those in Yugoslavia, Rwanda, North Korea, Burma, and Gaza. But taken at face value, The Rome Statute Explanatory Memorandum says crimes against humanity are:

“ … particularly odious offenses in that they constitute a serious attack on human dignity or grave humiliation or a degradation of one or more human beings. They are not isolated or sporadic events, but are part either of a government policy (although the perpetrators need not identify themselves with this policy) or of a wide practice of atrocities tolerated or condoned by a government or a de facto authority. However, murder, extermination, torture, rape, political, racial, or religious persecution and other inhumane acts reach the threshold of crimes against humanity only if they are part of a widespread or systematic practice.

A widespread or systematic practice.

I would like to invite any legal experts in this field – I have two law degrees including a PhD but this is not my field – for their opinion as to whether systematically continuing with widespread austerity against particular and especially vulnerable social groups in the face of clear evidence of its deadliness might constitute a crime against humanity. And point to whom, between 2010 and the present day, would and should be made most nervous by such enquiries, regardless of their political party membership.

The International Criminal Court would be unlikely to include the current UK situation in its scope – if they did, what other countries would be caught in that net? The context is simply too uncomfortable for them, the ultimately ‘slippery slope’. But that doesn’t mean discussion of this nature should be discouraged. A Labour government that promised no further austerity is committing further austerity, surely knowing full well that it will kill more people.

And the knowing? Is intent to kill. Makes it murder. It being social murder, being a government rather than an individual, isn’t a ‘get out of jail free’ card. Oh no, wait. Apparently it fucking well is.

Thank you @Rachel. Really powerful piece. We need to talk about social murder and not stop.