As too often happens in these rancid times, we were rudely interrupted last week by the continuing existence of frog-faced chancer Nigel Farage.

Now, where was I? Ah, yes, I was about to have to type the name of another odious human wrecking ball, who has not only gone unpunished for his many sins, but has been positively rewarded – the suspiciously sniffy slug-faced chancer Michael Gove. The things I do for you, honestly!

In the last episode, I introduced the story of how a small-to-medium enterprise (SME) registered in Cornwall was given a £70 billion contract to deliver the essential and urgent climate change goal ‘Net Zero’. That story was dropped by most press, as they found it was ‘just’ a framework contract, the insane financial figure having been plucked out of someone’s arse like an arrant g-string.

But me, I was unable to let this go, because I still wanted to know: who are these people? Why them? (Okay, and also because, autistic hyper-focus). I came across such a global rat’s nest that this is part two of three and probably four because we also need to see what everyone’s up to nowadays. Are they earning imaginary billions? The following was the case as of the summer of 2022.

Claire Delaney is a procurement expert and education sector consultant. She previously worked in client services, advertising, and design services. She was a director of the Crawley Free School Trust from December 2012 to January 2014. Simon Rule became a director on the same day, and remained one. Both became directors of Education Excellence For All Trust on 10 January 2013; she resigned in January 2016 and he resigned in January 2018. It was dissolved, and seems to have been turned into the Creating Tomorrow Multi Academy Trust. They are not a couple. She is very pretty. Her husband is smoking hot, just saying.

When you start looking into free schools, you come across the same names a fair bit. They work with each other in different companies and trust boards, sometimes leaving to start their own. Let’s pause for a brief primer on free schools, academy schools, and multi-academy trusts (MATs).

New Schools Network (NSN) was created by Boris Johnson and Michael Gove advisor Rachel Wolf in 2009. Gove was then Shadow Secretary of State at the Department for Education (DfE). Wolf visited New York and came across the idea of charter schools. By early the following year, hundreds of applicants had expressed an interest in free schools with the NSN; free schools were part of Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition government policy by June; and the first 24 such schools had opened by September of the year after that.

Academies and free schools are English state-funded, non-fee-paying schools, operating independently of local authorities and in accordance with funding agreements with the Secretary of State for Education. Maintained schools are old school local education authority (LEA)-run schools, many academies are ‘converter schools’ that used to be local authority schools, and free schools are, legally at least, a sub-species of academies. MATs are what they sound like: trusts that operate more than one academy but as single legal entities with one set of trustees. Some MATs run as many as 40 or more schools.

Academies don’t have to follow the national curriculum, though primary academies must participate in national curriculum assessments such as SATs. When hiring new staff, or if they’re brand new academies or free schools, trusts can determine their own staff pay, terms, and conditions for staff, in compliance with employment law and funding agreements.

New Labour started academies in deprived areas to improve equality of educational opportunity. But the Coalition government threw it wide open, enabling any school to convert, and forcing schools with a satisfactory or lower Ofsted grade to convert, even when most parents didn’t want that.

By 2013 there were 15 times as many academies as three years earlier; by now more than two-thirds of secondary schools are academies, or going to be, many in ‘chains’. Online reports extol how amazing academies and free schools are, but these are often commissioned by organisations in the business of them. In fact, there’s little to suggest academies do any better than regular old schools.

Many free schools are run by parents, and don’t have to employ qualified teachers. They don’t have to follow the national curriculum, though they must teach English, Maths, and Science. Some are faith schools, some are not.

Free schools can represent a duplication of resources, and are a drain on other local schools, in that students being withdrawn into them results in reduced funding. There’s evidence that free schools are of more benefit to children from higher income households, thereby employing public funds to increase social inequalities.

To summarise: these schools are still state-funded but are independent of local control, not answerable to local people, and run by charitable trusts accountable only to the Secretary of State for Education. They’re non-profit [for now] but more senior people involved can earn salaries far in excess of usual public servant rates.

Additionally:

The wonderful Michael Rosen suggested that school property which was part of taxpayer assets was handed by Michael Gove to his pals. Heist.

A 2017 National Audit Office report found free schools have a negative impact on surrounding schools, sometimes ‘cream off’ more privileged pupils, and are poor value for money. Yet they continue to be given more money than other schools despite scant evidence of superior performance. Heisty.

Some schools outside the old LEA model are run by obscenely rich Brexiteers. The Ultimate Heist.

Claire Delaney is the Managing Director of Place Group Ltd; the Google results summary also says ‘Owner’ but this disappears when you click through to LinkedIn. In August 2022 she was also a director of Place Group Consulting Ltd and Schools’ Buying Club, and Co-founder/Director/Chair of the Bellevue Place Education Trust.

Delaney once put out a call for staff on Facebook: “We're looking for two grads - Jnr data analyst and a marketing exec. If you know anyone that may be interested in a chat please let me know. Xx”. It’s unclear which of the four concerns needed them. A friend had to explain to her how to make the post shareable. Kiss kiss.

Before Delaney joined Place Group and free schools became a Gove passion project, co-founder Simon Rule was involved more in schools design, though was then described as an ‘electronic learning expert’. There was criticism by the National Union of Teachers of one learning space designed for a class of 60-90 students; the headteacher said it would rarely be used, so what was the point?

The Hunger Games? You just know they’re coming in English ‘education’.

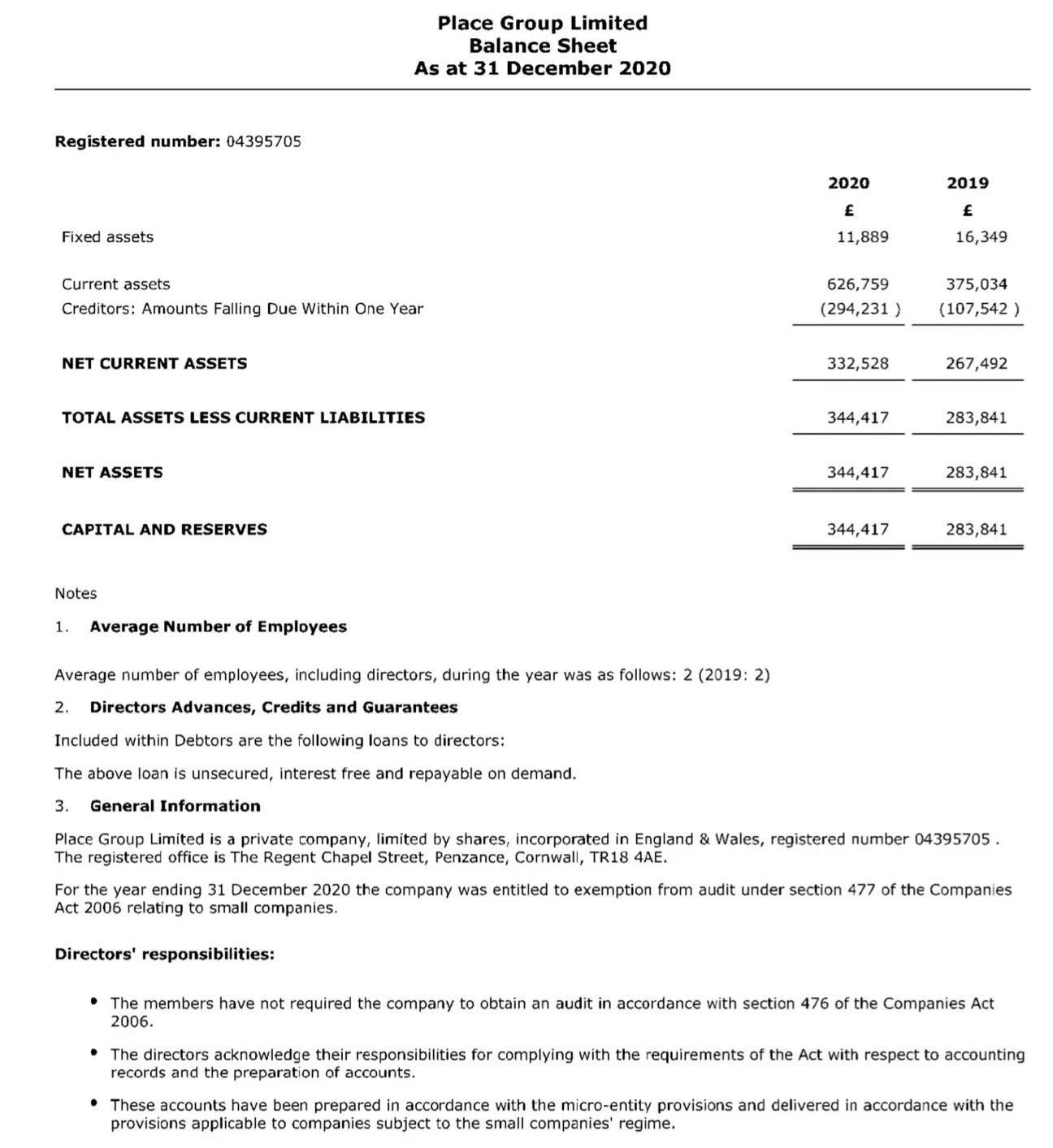

The two directors of Place Group Ltd (PGL) appeared from its accounts to be its sole employees, but its LinkedIn profile said it had 11-50 employees (as did Schools’ Buying Club; BPET had more employees and was ‘non-profit’). PGL was described as providing “consultancy, programme management and delivery services which are focused on driving the best possible outcomes for young people, their families and their communities. Our services have been designed to guide you and your stakeholders on a journey of transformation.”

A journey of transformation. Wear sensible shoes, bring water, bug spray.

Bellevue Place Education Trust (BPET) was founded in 2012, run by Bellevue Education and Place Group, to run primary ‘free schools’ in London and South East England, which have non-profit financial arrangements via a master funding agreement with the Department for Education (DfE). BPET’s first such school, Rutherford House in Balham, is where BPET is registered as existing, though the Rutherford website says it’s in Kilburn.

BPET partnered with philosopher AC Grayling on a free school, but that one didn’t work out. In 2014, BPET opened two more free schools in Islington and Maidenhead. It is a MAT, and as at June 2025 has 12 schools.

Their establishment has often attracted controversy. Poor consultation and use of public funds; ‘maddening and opaque’ processes and transfer of assets; concerns about diversion of pupil funds and education for profit; the imposition of national decision-making drowning out local assessment of need; and inappropriate location married with lack of transparency. Schools could be approved for go-ahead by Gove before there was even a site for them.

This reminds me of the Net Zero ‘procurement’ process, funnily enough: put the big picture in place first, worry about the details later, then do whatever to push things through. This was the case with at least one BPET school, which it was argued wasn’t even needed in that area, yet it became one of the most expensive in the country. And remember, its building was paid for from public funds.

This Guardian article is worth reading for two reasons: it highlights how much people running academy schools can be paid, which of course means less money going back into education provision and facilities, just as we’re seeing with water companies. It also gives details of a situation involving Delaney and Rule which highlights not corruption — there wasn’t enough transparency to reach a conclusion about it, Delaney basically saying “take our word for it” — but at the very least poor judgement.

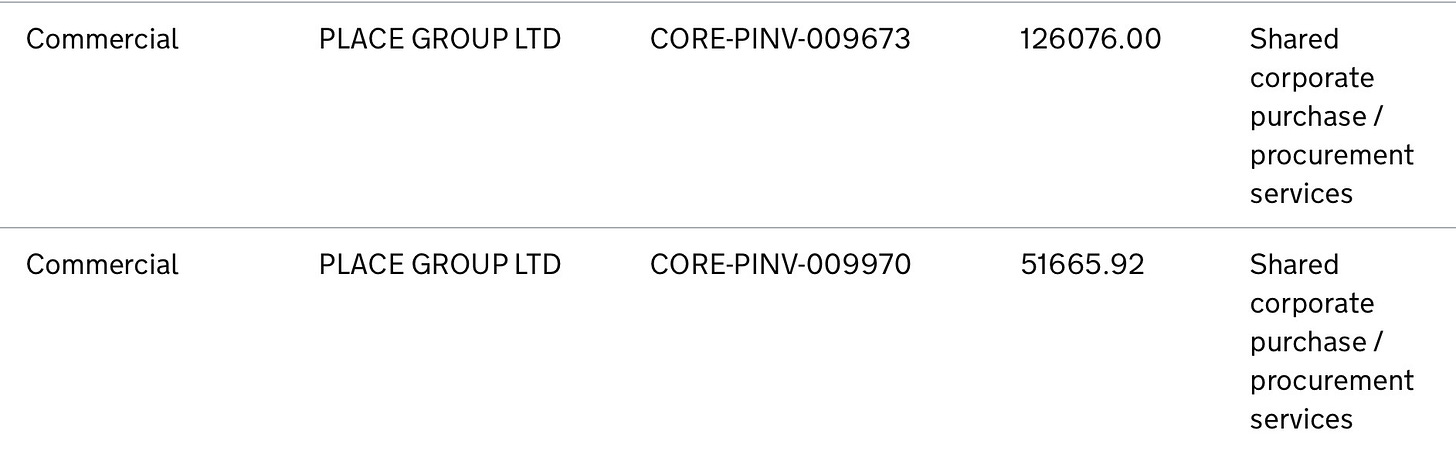

Under governmental rules, if an academy trust purchases services from a company run by a trustee of the very same academy chain, then it must be done ‘at cost’. In 2015, BPET made payments of £206,258 to a private consultancy for the setting up of four free schools. What was left out of the accounts was that the chair of trustees and another trustee of BPET, Claire Delaney and Simon Rule, were also managing director and chief executive of (and each a 22.5% shareholder in) the consultancy: Place Group.

Additionally, the procurement provider who decided which services the trust should buy was …? Schools’ Buying Club (SBC). The latter didn’t charge BPET for its work, however, ‘the successful provide [sic]’ was ‘charged as a percentage of the overall contract.’ Again, Delaney and Rule were SBC directors and each owned 22.5% shares.

‘Place Group’ commented that it and SBC had worked for BPET at a loss, and Delaney said they had “stepped away from any involvement” in the process. So which of their many many employees handled it? Both companies’ bids followed DfE guidance on what ‘at cost’ meant, she said, and the DfE was aware of all relationships and related transactions.

The chief executive of BPET, Mark Greatrex (invited by New Schools Network to become a founding member of its Free School Leader Network) said getting services ‘at cost’ led to significant savings. We have no way of knowing detailed facts, though, because PGL and SBC are registered as small enough companies that they need not be audited.

I guess if you have so many SMEs in the same sector, who can keep track of who’s selling what to who, amirite? I know I’d struggle. ADHD, what can I say.

Then BPET, of course, started making public ‘Net Zero’ noises, because Place Group was involved in Net Zero. Or was it the other way around?

“The ONLY topic of conversation is how schools meet zero carbon targets through improving buildings and encouraging behavioural change!”

Trustee Simon Rule

PGL tweeted for the first time about the environment in July 2021, then again in late September. Its occasional tweets mostly became about the environment, and it changed its header to an image with vaguely green-themed clip art on it.

I could be wrong, but to them it might have looked something like, ‘Hey, we can make money and make the world a better place, what’s not to like?’ If they don’t know all that much about tackling climate change, lacking a background or education in the relevant science, they must know people who do, and/or can ‘procure’ people who do, riiiight?

Other than concern for the environment, how do two people with four different-yet-interconnected education concerns get involved with Net Zero and sustainability in the first place? The clue may lie in the birth of Place Group itself.

Martin Chilcott is a serial entrepreneur, probably best known for founding the world’s largest sustainable business community, 2degrees. He got started by founding technology marketing consultancy CTSS, its main client being a then-humble little firm called The Carphone Warehouse.

Chilcott later founded a number of other concerns before starting Place Group in 2005, making it the UK market leader of school-academy transitions within three years. He gradually segued into interests in environmental programs and resource scarcity, founding first Meltwater Ventures then 2degrees, including its software platform Manufacture 2030. He resigned as a PGL director in 2012.

I am exhausted, and you probably are, too. So stay tuned for part three, which will create a place on the internet where BPET, Tony Blair, Swiss schools, Leonardo DiCaprio, the former chair of Ofsted, international money launderers, the trouble with filtering internet searches for ‘nude ladies’, Mossack Fonseca, American edu-grifters, the High Court, the powerrrrr of procurrrrrrrrement, and me, and you, can all meet up for bantz.

And for more of the spectator sport (for most of us) that Padraig Boocock calls “directing the nozzle of the public money siphon into the maw of the cronysphere”.